This article comments on findings from a survey of 1,151 respondents undertaken during July/August 2020 by the Institute for Applied Economics and Social Value (IAESV) and Centre for Urban Research on Austerity (CURA) at De Montfort University, Leicester. It explores a notable theme in the survey, the desire for a new programme of government with a more progressive, egalitarian and democratic character than the UK has seen perhaps for decades, and certainly since the global financial crisis of 2008-9. Whilst there has for some years been evidence of such a trend in public opinion, alongside a shift towards socially conservative values (also captured in the survey), the experience of the pandemic appears to have amplified the public appetite for change.

Asked whether government should return to business as usual, or introduce a new programme, 81.4% thought there should be a new programme of government. We then posed a succession of questions about what should happen in future, and what public governance priorities should be. Asked whether we should be placing a greater priority on socialism or free market capitalism, respondents were ambivalent. They were also ambivalent about the extent to which austerity had contributed to Britain’s lack of preparedness for COVID-19, with many neutral on the question and only a slight bias towards the view that it had been harmful. Nevertheless, there was pronounced support for a raft of measures that diverge from the austere public policy priorities of recent years.

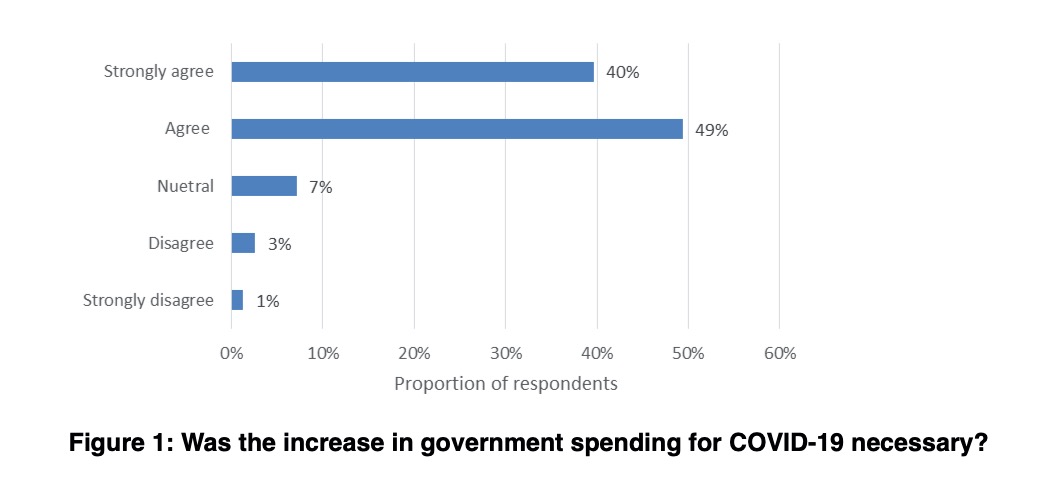

Spending in the Pandemic: We identified overwhelming public support for the increase in public spending in response to COVID-19 (88.9%), with further majority support for continuing higher spending for as long as the virus is a threat. There was less clarity about whether higher spending should continue longer-term regardless of whether the virus remains a threat. However, there was considerable support for increasing taxes on wealth and high incomes, along with a desire for greater social equality.

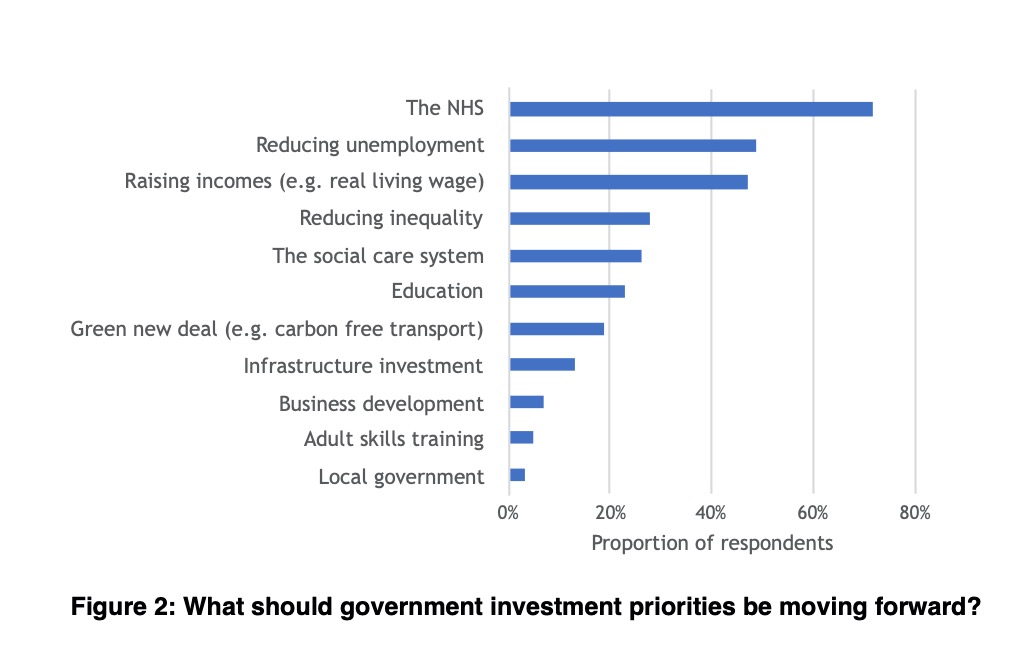

Forward Priorities: As to what Britain’s national priorities should be in the coming decade, driving economic growth and funding world class public services topped the list, especially more funding for the NHS. Greater equality was a high or medium priority for a large majority, so too preparing for future crises – perhaps unsurprisingly given the pessimism also expressed about long-term prospects for the UK and the world. Tackling climate change was a high priority, though support for government investment in a “green new deal” was not as high as this level of concern might have suggested. Asked about how views had changed since the pandemic, respondents indicated that they were more in favour of NHS investment, infrastructure spending, higher taxes and spending than they had been beforehand.

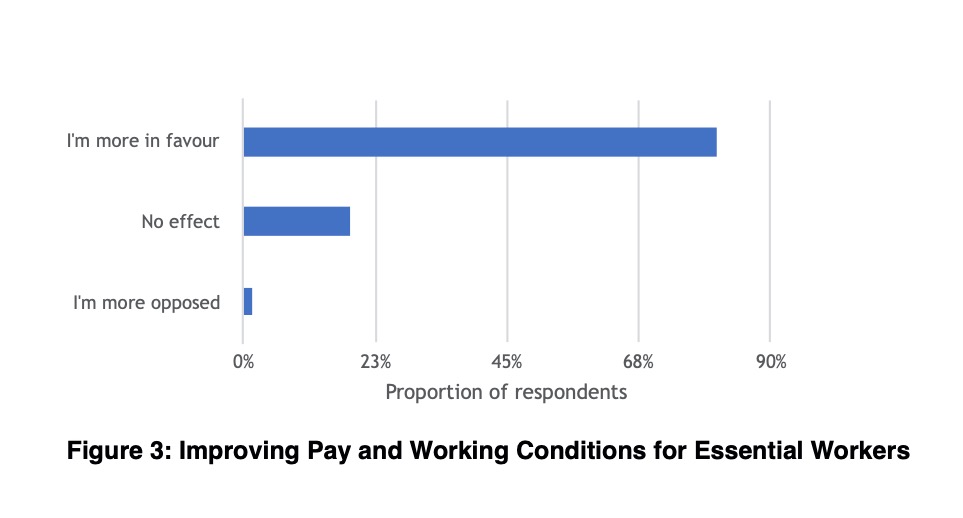

Work and Workers: A significant majority indicated that all workers should be paid a decent living wage and investing in job quality was a priority. Respondents saw class inequality as a significant problem and held positive views about essential and key workers, indicating that improved pay and conditions should be a priority for this group. Views towards overseas workers accessing free health care were positive, and a significant percentage of respondents indicated they had gained a new appreciation for the role of foreign workers during the pandemic. Perhaps surprisingly, a majority reported that they were more in favour of government spending on welfare and benefits than before, with nearly 50% saying they favoured payments regardless of individual need.

Given common demographic and political biases in surveys, the findings should be treated with a degree of caution. Nevertheless, it is clear enough that there is no appetite for a return to austerity, and that there is an appetite for a new political-economic order. Politicians and commentators have tried to capture this sentiment, summoning the ghost of Roosevelt and the New Deal, while the Financial Times, fearful of rising alienation and social fracture, calls for a new “social contract”. The survey tacitly supports the view expressed by Dominic Cummings, that a majority would happily fleece the bankers and invest the money in the NHS, while also supporting socially conservative policies.

However, for a Conservative Party long wedded to preaching the evils of big government, tax and spend, the public demand for economic progressivism is likely to be extremely divisive, unlike the social conservative impulses with which many of its MPs and members in any case sympathise. However, as the Conservatives at least gesture to a more expansive role for the state in “levelling up”, Keir Starmer’s Labour Party is left with a puzzle about how to position itself. How can it plausibly oppose an agenda that it also espouses, albeit in a different form? What distinctive political ground can a party committed to moderating its post-Corbyn offer plausibly claim? How does Labour fight to reclaim the progressivist ground that it used to own? If Boris Johnson is the unlikely face of a 21st century “New Deal”, does it oblige Labour to try and set out its own distinctive view of what this could mean under a Starmer government? Perhaps Labour strategists believe the party is better off keeping its counsel in the hope that a tired and lacklustre PM, heading a fractious party in a terrible public health and economic crisis, will eventually be hoist on his own petard. Electoral success for any party in the near future will depend on the ability to shape, challenge and respond to a new political conjuncture, crystallising at a most extraordinary point in the UK’s history.

Professor Jonathan Davies

Professor Edward Cartwright

Dr Arianna Giovannini

Dr Jonathan Rose