How the sharing economy hollowed out Brooklyn?

By @DMUpolitics student Michaela Cracknell /@kyliecracknell

CURA is proud to publish outstanding student contributions pertaining to pressing issues facing cities today. In this blog, MA Politics student Michaela Cracknell explores the relationship between gentrification, Airbnb and tenant displacement, in an historic neirbourhood known as Crown Heights in Brooklyn.

Image from: https://www.bsdcorp.org/2016/03/bridge-street-is-at-the-forefront-of-preventing-tenant-displacement/

“I’ve seen it when nobody wanted to live here,” she said. “As soon as I started to rent an apartment, the rents went up, and now it’s like we’re not even good enough to stay in the neighborhood anymore.” These are the words of long-time Crown Heights resident Angelique Coward from an opinion piece interview in the New York Times.

Ms. Coward is one of many residents from the Crown Heights community that was forced out of her home by rising rents (a 39% increase from 2010 to 2018[1])[2] and pressure from landlords to make room for those with deeper pockets.

Gentrification in this historic Brooklyn neighborhood has made it a desirable location for further investment into the tourism industry including a spike in ‘AirBnB’ rental properties. However the increases in this sector of tourism has had a negative effect on the amount of affordable housing in the area.

Gentrification in Crown Heights

The gentrification issue is effecting formerly low income neighborhoods all over the world, Crown Heights is just one example of the issue at its worst. But what do we mean we say the “gentrification issue”? Clinical Psychologist David Ley simply defines it as “a transition of inner-city neighborhoods from a status of relative poverty and limited property investment to a state of commodification and reinvestment.” [1]

In Crown Heights we can see this transition by looking at the rise of expensive bars and restaurants, art galleries, and coffee shops that are replacing food markets and affordable corner stores. We can also look the aforementioned rising rent costs in the area. According to an MNS market report, from 2015 to 2016, Crown Heights saw the largest increase in rent of any Brooklyn neighborhood (7.6% increase).[2] But is gentrification a bad thing? Urban theorist Loretta Lees would say yes, citing that gentrification leads to deeper social segregation and displacement[3].

For Crown Heights, that has become reality with poorer minority groups being forced out of the inner city to make room for a growing affluent presence. This displacement of these groups in larger cities contributes to an acute friction in social and racial relations that already runs deep in the United States. This tension can be even further amplified when areas that once served as havens for those surviving on lower incomes are turned into profitable epicenters for wealthy investors and developers.

The Role of Airbnb

Gentrification also often leads to an area becoming more popular to tourists and this can open the door for in investors in different sectors of tourism industry like for example the hospitality/accommodation sector of the ‘sharing’ economy.

This new ‘sharing’ economy can be defined as a sharing, exchanging or renting of goods, services and properties by individuals. Meaning individuals are able to share what they own or a service they can provide with others for a profit. This could be something as simple as washing someone’s car or renting your home out to tourists.

Some economists, like Martin Weitzman, argue that this new economy could end stagflation effect and create an equilibrium among wages[1]. While we can‘t ignore the positive benefits of this new system on the microeconomics of the urban area, what are the costs? In the case of Crown Heights, it’s displacement due to a lack of affordable housing.

‘AirBnB’ is just one of many popular platforms for the sharing of individual’s properties as temporary holiday rentals for tourists and travelers. These types of accommodation are becoming increasingly popular in desirable global cities like New York. AirDNA has compiled extensive data on ‘AirBnB’ properties in Crown Heights. Their data reveals that since 2010 there has been a nearly a 25,000% increase in AirBnB rentals in the neighborhood. With rental properties exploding and rents rising in Crown Heights, it leads one to ask, where can people actually live, affordably?

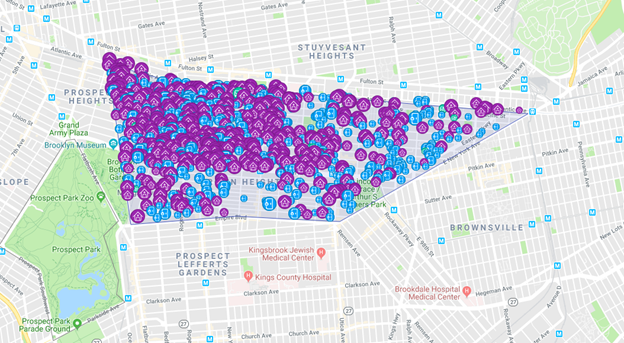

According to AirDNA, there are currently 1,090 active ‘AirBnB’ rentals in Crown Heights

https://www.airdna.co/vacation-rental-data/app/us/new-york/new-york/crown-heights/overview

Challenges to Gentrification

The answer to that question, unfortunately, is nowhere. Of the 1,090 active Airbnb rental properties in Crown Heights over 50% of them are entire home rentals. Meaning that properties that could serve as much needed affordable housing, are being used as strictly for-profit holiday rentals. This is where we see the correlation between Airbnb and displacement.

People who have grown up and lived their whole lives in Crown Heights are being forced into other boroughs, out of New York all together, or on the streets due to lack of affordable housing. A report from New York’s Independent Budget Office found that from 2002-2012 families entering homeless shelters came in largest numbers from East New York, Bedford Stuyvesant Heights and Crown Heights.[1]

But the community is beginning to fight back against this inequality of housing. The Crown Heights Tenant Union, founded in 2014, has become active in protesting to demand protection for low-income tenants, fair rent prices and rights to repairs. They currently have over 40 member buildings and continue to hold peaceful demonstrations to fight against rampant gentrification, displacement, and illegal rental overcharges.[2]

The urban has always been the epicenter of

progress and not many would argue that progress is a bad thing. However, often

there are those who get left behind as the world marches forward. Crown Heights

is becoming gentrified as New York progresses to a more global city attracting

people and investments from all over the world. Though these investments,

specifically those is the Airbnb market, are causing residents to be displaced

due to a lack of affordable housing.

[1] New York City Independent Budget Office (2014). Fisical Report. [online] New York. Available at: https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/2014dhs.pdf [Accessed 23 Feb. 2019].

[2] Crown Heights Tenant Union. (2015). Crown Heights Tenant Union – About Us. [online] Available at: https://www.crownheightstenantunion.org/about-us [Accessed 23 Feb. 2019].

[1] Weitzman, M. L. (1986) ‘The Share Economy: Conquering Stagflation’, ILR Review, 39(2), pp. 285–290. doi: 10.1177/001979398603900210.

[1] Ley, D. (2003) ‘Artists, Aestheticisation and the Field of Gentrification’, Urban Studies, 40(12), pp. 2527–2544. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000136192.

[2] MNS. 2016. “Brooklyn Rental Market Report”. MNS. http://www.mns.com/pdf/brooklyn_market_report_feb_16.pdf.

[3] Lees, Loretta, Tom Slater, and Elvin Wyly. Gentrification. Routledge, 2013.

[1] “Uneven Burdens: How Rising Rents Impact

Families And Low-Income New Yorkers”. 2018. Blog. Trends & Data.

https://streeteasy.com/blog/nyc-rent-affordability-2018/.

[2] Yee, V. (2015). Gentrification in a Brooklyn

Neighborhood Forces Residents to Move On. The New York Times.